I'm Sorry, I Don't Speak English

Photo courtesy of author

By Anonymous (she/her)

Adoptee, 31

From Wuhan, China; Living in Vancouver, BC Canada

View the accompanying zine here.

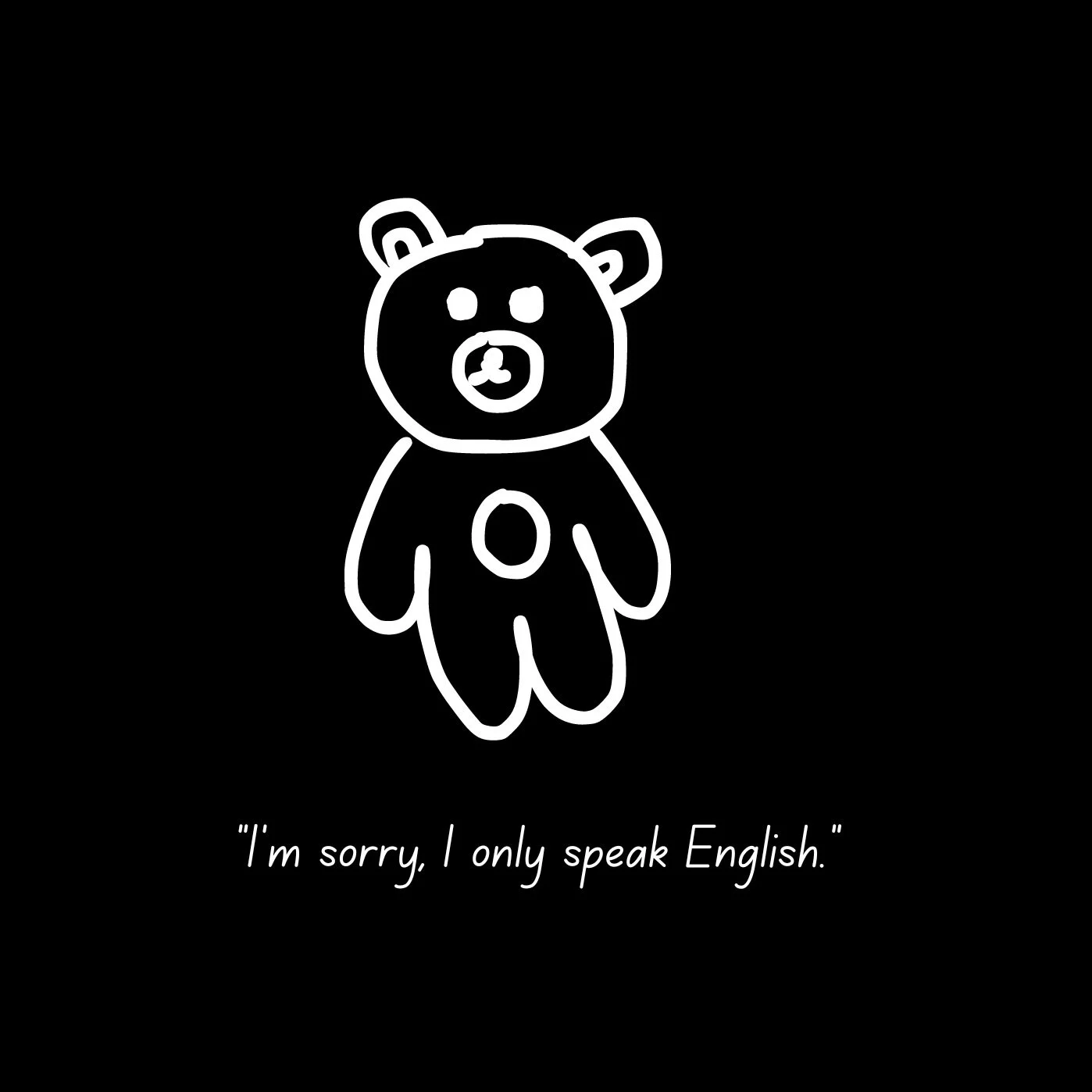

“I’m sorry, I only speak English.”

Previously, remarks like “you’re basically a White girl inside” or my disclosure of “I’m adopted” have felt insignificant at the time, but recently these voices, including my own, have grown louder. In these seemingly ordinary moments, I grappled with the impact of my Chinese adoptee experience and its connection to my dual Chinese-White identity. Despite early childhood efforts by my parents to encourage an appreciation for my Chinese culture, I distanced myself in high school where more Western-centric perspectives shaped my identity. Identifying myself closely with Whiteness used to evoke pride, while acknowledging my adopted status left me feeling like an outsider and experiencing a sense of disconnection. However, I have recently felt a growing sense of detachment from Whiteness and Canadianness when I have been on the receiving end of racist interactions or in discussions around race. Now, this feeling of overall disconnection in my dual identity is amplified, intertwined with a lingering grief stemming from the absence of strong bonds to my Chinese origins. Reflecting deeply on these past and present moments forces me to confront my dual identity filled with disconnectedness, where the path forward remains unclear.

In the 2016 film "Spa Night" about a closeted Korean-American teenager, the main character, David’s, lack of dialogue provoked a more introspective reflection from the audience, which influenced the minimal design element choices in my zine. Viewing his experience as a body in the world instead of through frequent conversations connects to my adoptee experience in reflecting on the small remarks people have said to me and how I experience the world through my dual identity. This also relates to the way David negotiates his Korean-queer identity and reimagines it in different ways throughout the film.

Using a digital zine with a black background, white font to display the quoted remarks, and a hand-drawn childhood toy bear, my aim is to strip away any design element distractions and focus on expressing the feeling of built-up confusion, shame, and disconnection over my own perception of my unbalanced dual identity. The drawn toy bear represents the only possession that came with me during my adoption and is hidden away in my childhood home – out of sight, but faintly in my mind over the years. Its presence portrays my Chinese-adoptee experience that has played a background role in my life, and perhaps Chineseness itself that exists but has not been fully explored. Thus, the growing size of the bear in the zine symbolizes “baggage” in the form of something that I have carried throughout my life without fully understanding what it means, until I was pushed to acknowledge the discomfort of not knowing and face an overwhelming identity disconnection.

The zine begins with other people’s remarks and eventually my voice interjects with the constant need to explain that I am adopted – each quote is short, yet memorable to me as they represent a snapshot of where I felt a dissociation within myself. As the pages progress, each consecutive quote and toy bear graphic increase in font and size, representing a growing and harder-to-ignore emotional impact. The last quote, “I’m sorry, I only speak English” coupled with the large size of the bear stresses to both the audience and me that the shame associated with my identity is now impossible to ignore.

The final set of pages display all the quotes and bear graphics overlapping each other to signify the built-up effect these everyday moments have had on me. I left out explicit reflection explanations of the quotes so that they convey a feeling of disconnection and encourages the reader to reflect on the impact of how seemingly casual remarks can shape how an adoptee negotiates and constructs their dual identity. Additionally, audiences with diasporic roots may resonate with the emotions of disorientation, grief, or identity conflict as their ties to their origins undergo constant scrutiny.

Along with the sense of identity disorientation, there has been an underlying fear whose origin I could not recognize. Through this project I discovered it was a fear that dismantling my current identity would somehow unravel and undo the pivotal self-work I have put in. However, I have come to the realization that delving deeper into my Chinese origins could be an enriching addition to my identity, rather than a subtraction from it. Despite the overwhelming sense of identity disconnection coming to a head, one thing has always been clear to me: there was never a question of whether my adopted parents were my “real parents.”

Author and Professor, Eleana Kim’s discussion around adoptees’ experiences encouraged me to reflect on what kinship means – while biological parents are the norm of what is socially recognized as a family unit that naturally supports each other, my adopted parents have always been my “real parents” or simply my parents who have loved and supported me no matter what. This familial bond goes beyond biological ties, prompting me to reflect that my experience as a Chinese adoptee is not confined by a binary perception, where my identity must connect either to my biological roots or adoptive family. This built up feeling of disorientation has propelled me to find a sense of security and trust within myself, allowing for the possibility of embracing both connections, however that may look. This feeling is emulated through the last page in the zine as the bear embraces itself in a hug, representing care and support towards and within myself as I work towards accepting all parts of my identity.

The views expressed in blog posts reflect those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the shared views of The Nanchang Project as a whole.

Our blog stories come from readers like you!

We invite you to send us your own story to share. We accept submissions from anyone whose life may have been touched by Chinese international adoption including, but not limited to: adoptees, adoptive families, birth families, friends, searchers.

Details in the link below!